Auxin transport – PIN-pointing the conserved mechanisms of plant pattering

Relying on model organisms can confound our understanding of biological processes. Our lab found this to be true for auxin transport, a pivotal patterning mechanism in plants.

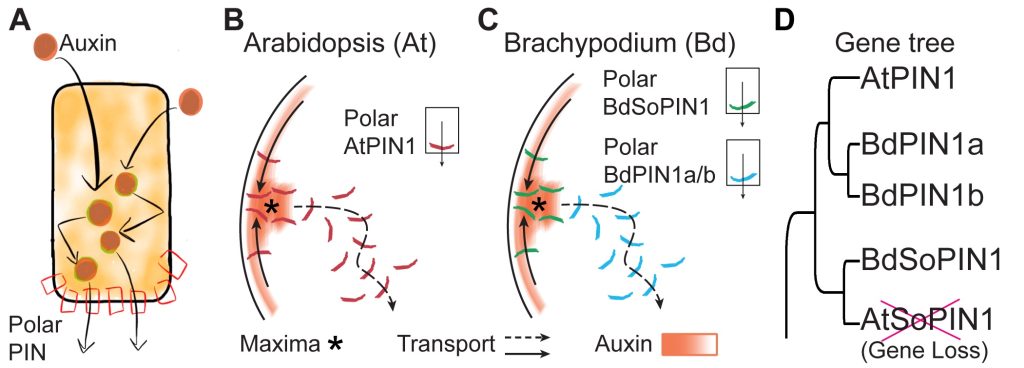

The hormone auxin can passively enter cells, but it cannot exit without active transport. Polar localization of the PIN-formed (PIN) efflux proteins controls auxin transport rate and direction during development (A). PIN proteins create auxin gradients and concentration maxima that direct how and where plant organs form. The principles underlying PIN polarization are not fully understood but are critically important as they underlie all plant growth and development.

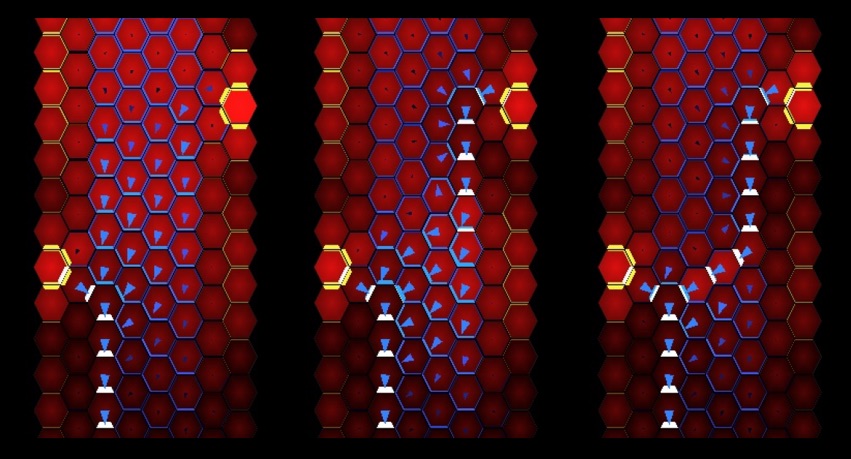

Most research on PIN-mediated patterning has focused on the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (At). During organ initiation in Arabidopsis, PIN1 (AtPIN1) polarization is organized into convergent patterns that concentrate auxin into the local maxima required for organ initiation. Paradoxically, later in development, AtPIN1 polarity inverts, forming narrow channels of transport away from maxima during tissue patterning (B). We can computationally model these two polarization behaviors with two different positive feedback loops with respect to auxin. Convergent PIN patterns are formed by PIN polarization up-the-gradient (UTG), orienting towards the neighboring cell with the highest auxin concentration. While polarization away from the maxima is modeled with-the-flux (WTF), with PIN polarized in the direction of the greatest auxin efflux (Model visualization below). Understanding the molecular nature of these different polarization modes is integral to understanding how plants create positional information during development.

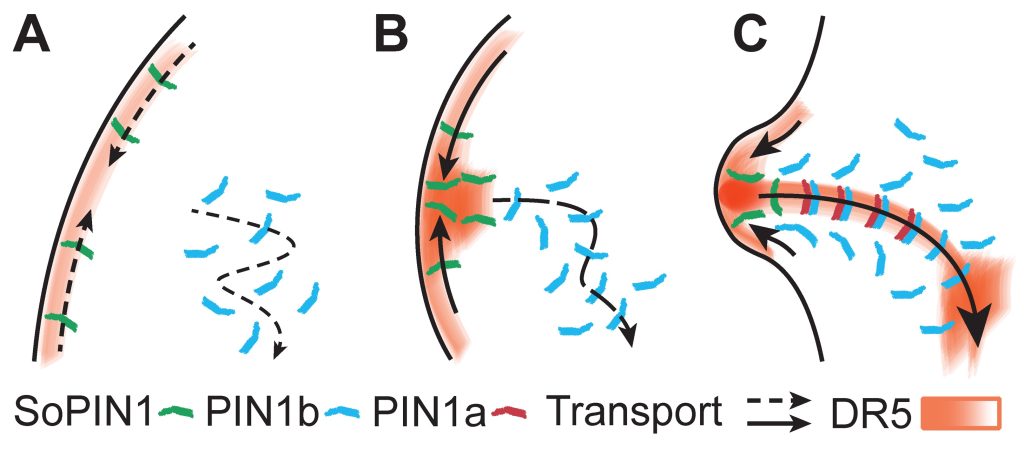

Remarkably, our data show that Arabidopsis is unusual in utilizing a single PIN to mediate both polarization modes. We discovered that in most other plants UTG and WTF polarization behaviors are split between different PIN clades, allowing us to molecularly separate the two polarization behaviors (C-D). By leveraging this split, we now have the tools to dissect the molecular nature of differential PIN polarization with respect to auxin as well as provide a more comprehensive understanding of auxin transport across diverse plant species.

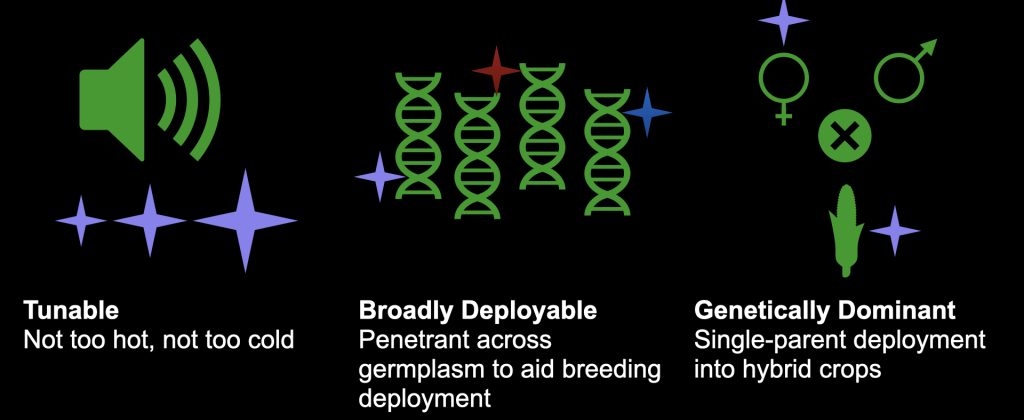

Allele Design – Tunable and genetically dominant crop improvement

The advent of new genome editing tools has enabled the controlled deployment of mutation for crop improvement. New tools offer precise control of DNA nucleotide sequence and the potential for rational allele design. We leverage these new editing tools and an “industry-like” gene editing pipeline in both Arabidopsis and Brachypodium to study how plant signaling pathways create graded or tunable outputs, and how alleles can have genetically dominant effects on phenotype.

Tunable signaling responses are important for plants to maintain proper growth, especially when regulating the stem cell pool. Moreover, tunable engineered alleles show the potential to optimize trait deployment in commercial crops such as maize because they can mitigate pleiotropic or compensatory phenotypes such as severe fasciation, decreased ear length, plant height, and kernel size.

Dominant alleles are important for crop gene edit deployment. In short, a single genetically dominant edit can do what recessive edits cannot when deployed in species where redundancy, hybrids, and clonal propagation make single recessive edits useless. Unfortunately, examples of dominant mutations are relatively rare in mutant collections, despite dominant mutations being integral to plant evolutionary transitions and agricultural innovation.

We leverage our edit pipeline to invent, publish, patent, and deploy tunable and genetically dominant gene-editing strategies for use in crop species.

Publications

Patterson E, MacGregor DR, Heeney MM, Gallagher J, O’Connor D, Nuesslein B, Bartlett ME. 2025. Developmental constraint underlies the replicated evolution of grass awns. N Phytol 245:835–848. doi:10.1111/nph.20268

Fusi R, Milner SG, Rosignoli S, Bovina R, Teixeira CDJV, Lou H, Atkinson BS, Borkar AN, York LM, Jones DH, Sturrock CJ, Stein N, Mascher M, Tuberosa R, O’Connor D, Bennett MJ, Bishopp A, Salvi S, Bhosale R. 2024. The auxin efflux carrier PIN1a regulates vascular patterning in cereal roots. N Phytol 244:104–115. doi:10.1111/nph.19777

Teixeira C de JV, Bellande K, Schuren A van der, O’Connor D, Hardtke CS, Vermeer JEM. 2024. An atlas of Brachypodium distachyon lateral root development. Biol Open 13:bio060531. doi:10.1242/bio.060531

Buendia L, Maillet F, O’Connor DL, van de Kerkhove Q, Danoun S, Gough C, Lefebvre B, Bensmihen S. 2018. LCOs promote lateral root formation and modify auxin homeostasis in Brachypodium distachyon. New Phytologist doi:10.1111/nph.15551

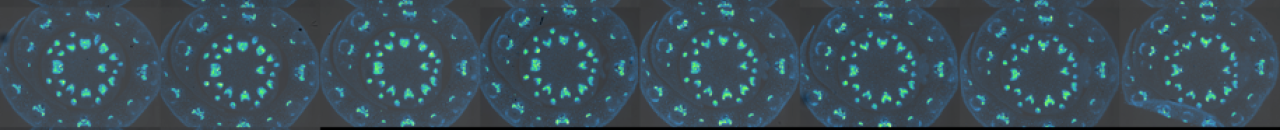

O’Connor, DL*. 2018. Live Confocal Imaging of Brachypodium Spikelet Meristems. Bio-protocol doi:10.21769/BioProtoc.3026

O’Connor DL*,Elton S,Ticchiarelli F, Hsia M, Vogel JP,Leyser OH. 2017. Cross-species functional diversity within the PIN auxin efflux protein family. eLife 2017;6:e31804.

Abraham Juárez MJ, Hernández Cárdenas R, Santoyo Villa JN, O’Connor D, Sluis A, Hake S, et al. 2015. Functionally different PIN proteins control auxin flux during bulbil development in Agave tequilana. J Exp Bot. doi:10.1093/jxb/erv191

Bennett TA, Liu MM, Aoyama T, Bierfreund NM, Braun M, Coudert Y, Dennis RJ, O’Connor D, Wang XY, White CD, et al. 2014. Plasma Membrane-Targeted PIN Proteins Drive Shoot Development in a Moss. Current Biology.

O’Connor DL*, Runions A, Sluis A, Bragg J, Vogel JP, Prusinkiewicz P, Hake S. 2014. A division in PIN-mediated auxin patterning during organ initiation in grasses. PLoS Comput Biol 10: e1003447.

Bolduc N, O’Connor D, Moon J, Lewis M, Hake S. 2012. How to pattern a leaf. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology 77: 47–51.

Bolduc N, Yilmaz A, Mejia-Guerra MK, Morohashi K, O’Connor D, Grotewold E, Hake S. 2012. Unraveling the KNOTTED1 regulatory network in maize meristems. Genes Dev 26: 1685–1690.

Chuck G, O’Connor D. 2010. Small RNAs going the distance during plant development. Curr Opin Plant Biol 13: 40–45.

International Brachypodium Initiative. 2010. Genome sequencing and analysis of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. Nature 463: 763–768.